Food Waste Reduction Program Inspires Middle Schoolers to Engage

Welcome to our blog series, CEE-Change, Together. Each month, NAAEE will post narratives from the CEE-Change Fellows as they implement their community action projects and work to strengthen environmental education and civic engagement capabilities, all supporting the mission of cleaner air, land, and water. Join us on their journey! The Civics and Environmental Education (CEE) Change Fellowship is NAAEE’s newest initiative to support leadership and innovation in civics and environmental education in North America. This ee360 program is a partnership between NAAEE, US EPA, and the Cedar Tree Foundation.

On behalf of the NAAEE Communications team, Carrie Albright had the opportunity to talk with 7th-grade science and social studies teacher and CEE-Change Fellow, Angela Rivera Rautmann. Angela created a community action project to provide students with an opportunity to not only dive into the sustainability issue of food waste but to also build skills that allowed them to share their findings with their community.

(Appreciation to the Sun Prairie Area Schools Global Good and Sustainability Podcast for student excerpts).

Listen to the Interview

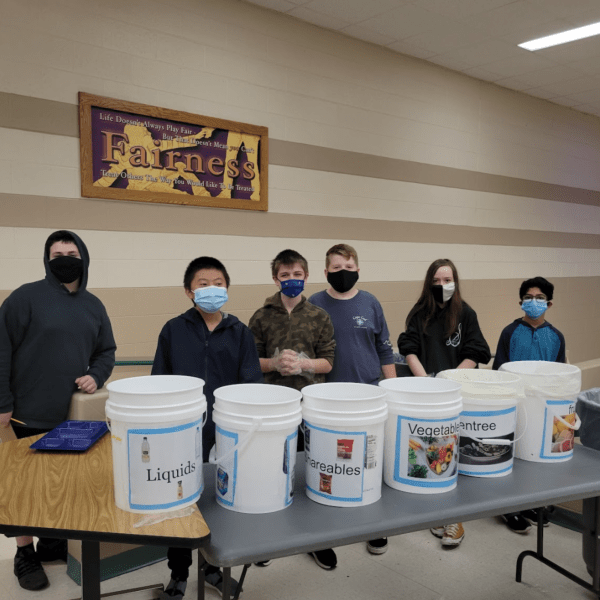

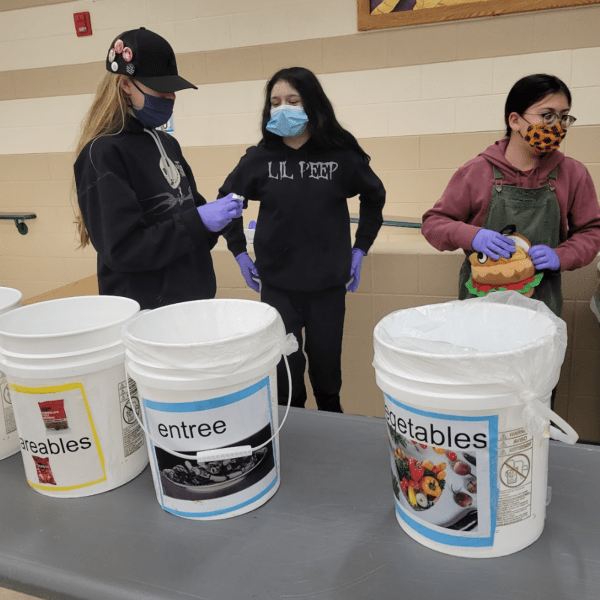

Food Waste Reduction Photo Gallery

Transcript

Angela Rivera Rautmann:

They would sort everything, and they were somewhat grossed out by it. There's a lot of 'ew' and I'm like, “You volunteered for this. It's okay.”

Student voice:

I was talking to my parents and I was like, “Maybe we could do a composting pile in our backyard."

Carrie Albright, NAAEE:

How do students go from being totally grossed out to personally invested in food waste reduction? We'll find out.

The Cedar Tree Foundation and ee360—a cooperative agreement with NAAEE, the U.S. EPA, and partner organizations—launched the CEE-Change Fellowship to scale up our impact as we work to create a more equitable and sustainable future. The CEE-Change Fellowship initiative supports leadership and innovation in civics and environmental education across North America. These educators foster leadership within schools and at the community level, promoting civic engagement and environmental responsibility, and ultimately building more resilient and healthy communities. On behalf of the NAAEE Communications team, I had the opportunity to talk with one CEE-Change Fellow, Angela Rivera Rautmann. As a 7th-grade science and social studies teacher at Patrick Marsh Middle School for the 2021–2022 school year, Angela's community action project provided students with an opportunity to not only dive into the sustainability issue of food waste, but to build skills that allowed them to share their findings with their community.

Angela:

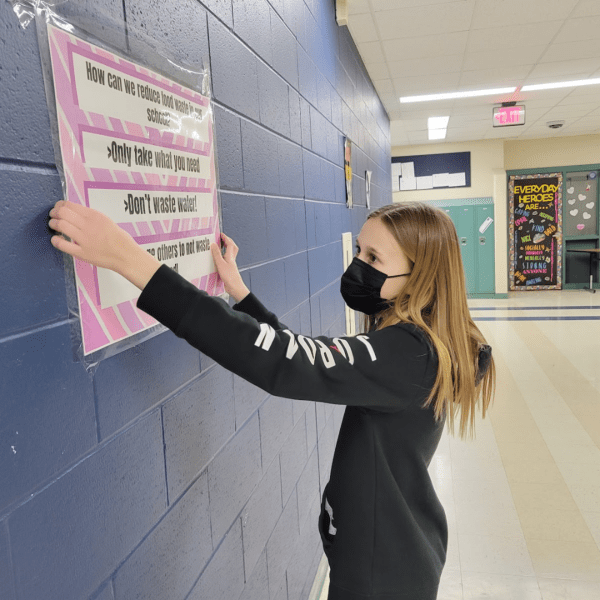

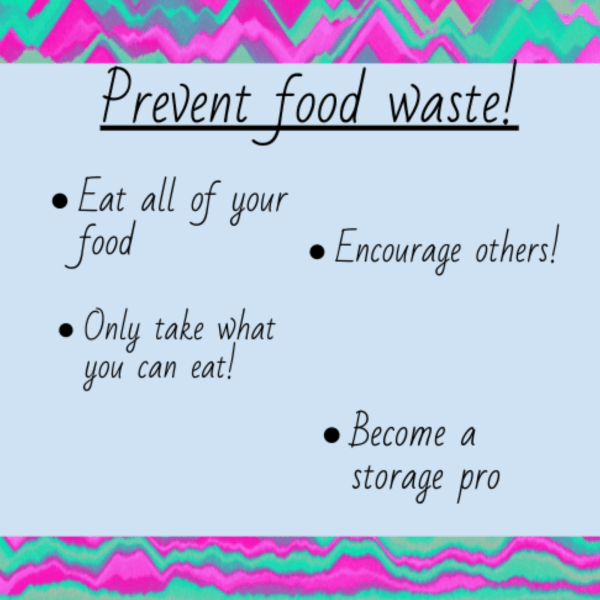

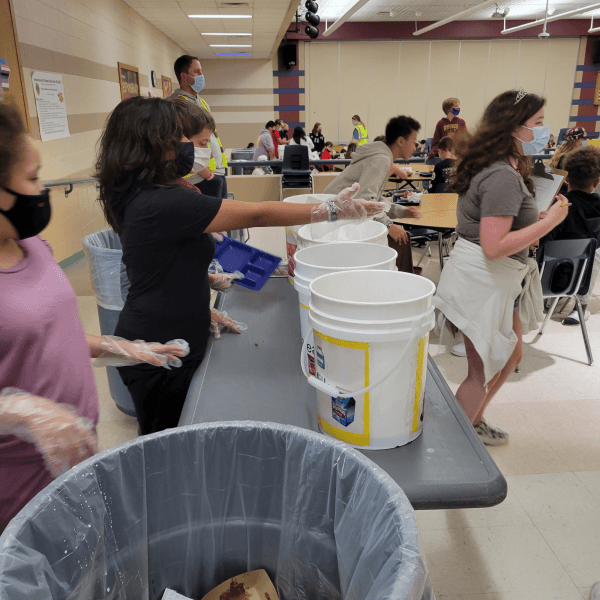

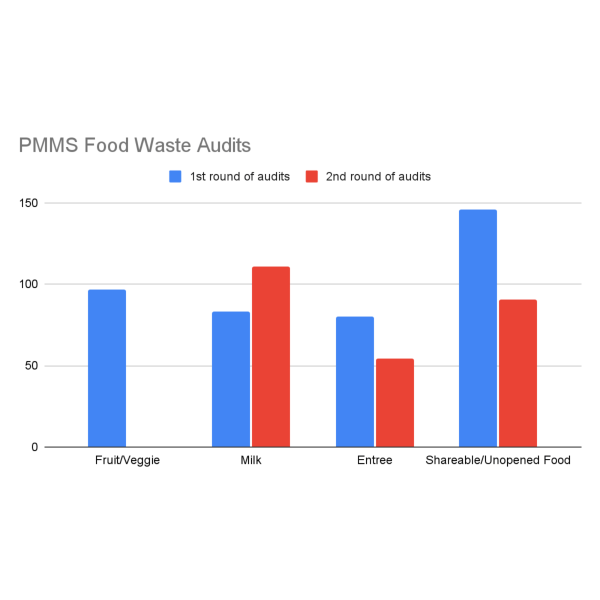

Last spring I got a fellowship through NAAEE, which is the North American Association for Environmental Education, to do a community action project. Part of that project was collecting food waste and analyzing food waste at our school, but also having the students kind of share their findings and how the community can reduce their own food waste which led to the ending composting presentation that they did. I wanted them to collect data at the beginning. I wanted them to look at their data and then actually come up with the changes they wanted to implement. Then I wanted them to do the audit again to actually measure their change, so actually have physical data of this is how much food is wasted and because we made these changes this is what we saw.

Carrie:

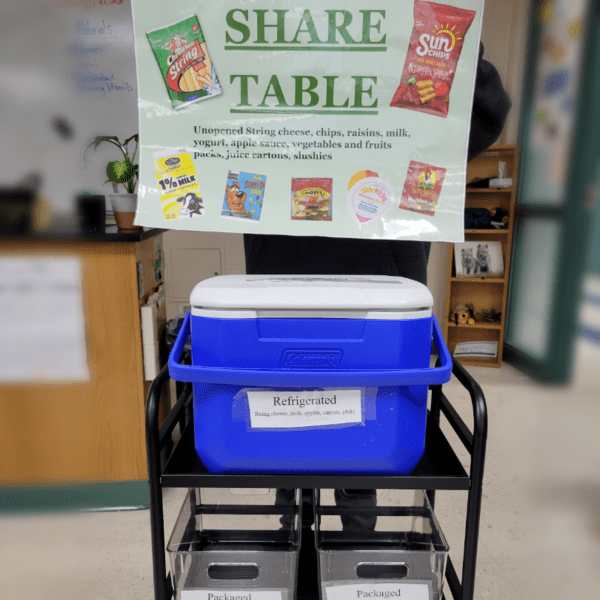

Okay, the “food share” table—What exactly is that and how does it work in a cafeteria filled with students?

Angela:

The food share table is a table within the cafeteria where people can put unopened prepackaged food. It also contains whole fruits that have a peel, like a banana. Ideally, people could put stuff on the table, and then people later in the lunch can take stuff off. The way that we have permission for it was that we could use it as a “No, Thank You” table so students would put things on, and then all those items would be donated to our community school program.

I had to get permission through the Food Service team in the district to do that. I had contacted the Food Service person. I was like “Here's all the data we collected. We really would like to do a Food Share table and here's why and here's my background.” I had worked in waste reduction in my previous job in Cincinnati, so I kind of have this background of like helping schools kind of understand the USDA guidelines, as well as I knew I had to look at the state guidelines in Wisconsin. I went through that process to make sure I knew all those things and then I approached her with like, “Here's the data, here's how much food we reduced by implementing a food share table.” She was willing to work with me and talk through it so we decided on a “No, Thank You” table instead of the more movements of items within the cafeteria. She made sure we contacted the Health Departments and was willing to let us try it.

The students really wanted to use it. It was used a lot by students, it really was. I saw a lot of movement. I would go in there to observe, especially at the end of my lunchtime, and of my students. I would take the Food Share table to the Community Schools person who's saving it to be redistributed. I saw so many things leave the table that we probably would have donated a lot more. But it was okay that we didn't because students were eating it and that's the whole point. So I think that's kind of where we’re at. I think the data really helps with all that piece. You need to have proof of why this would be helpful especially when it comes to having to change regulations and follow Health Department guidelines. I think that's what pushed it over the edge, not only that I have a background in waste, but also I have the data, the proof that we were wasting so much food and that we could redistribute it to somebody else.

Carrie:

What do you think the students took away from the experience of this Food Waste Reduction program?

Angela:

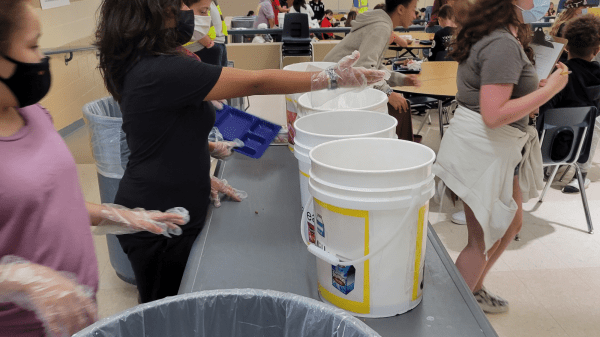

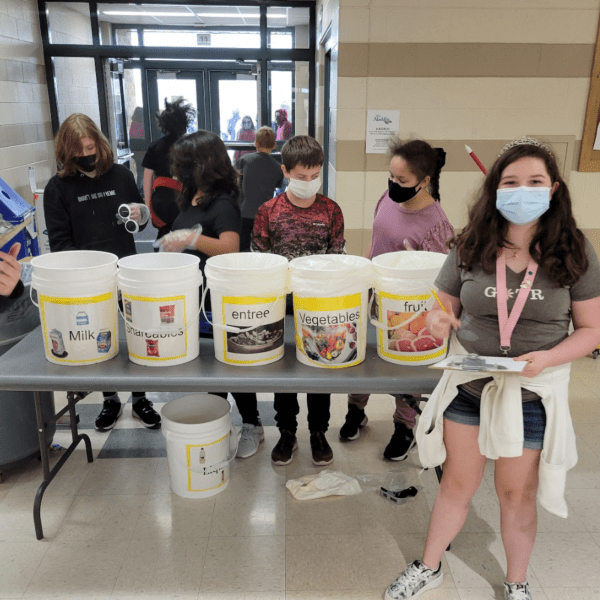

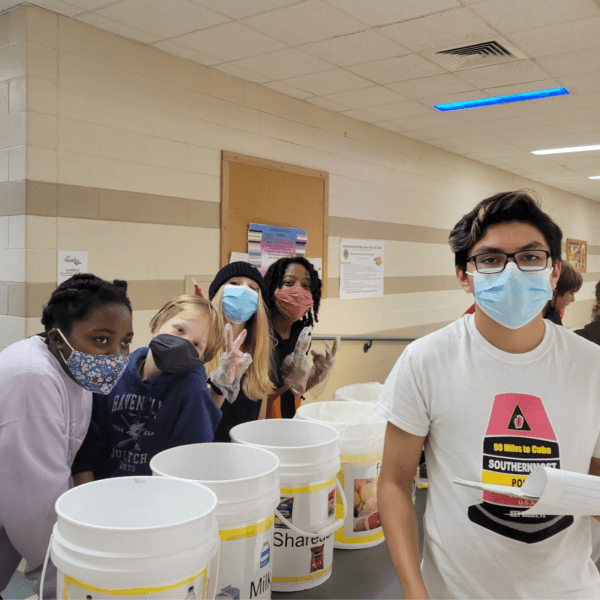

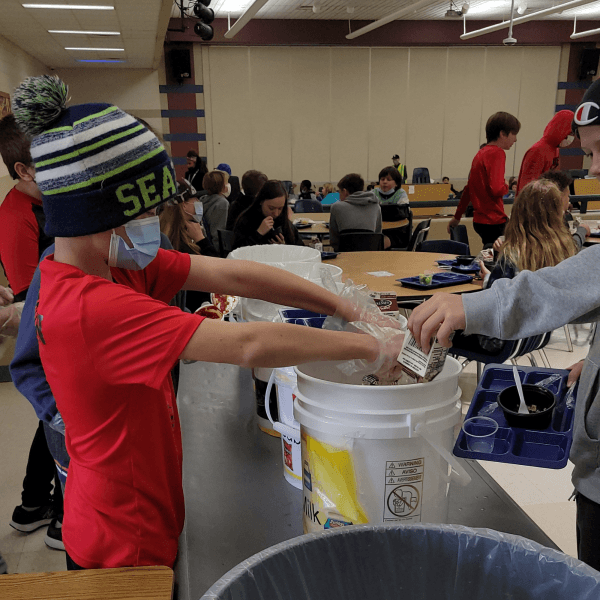

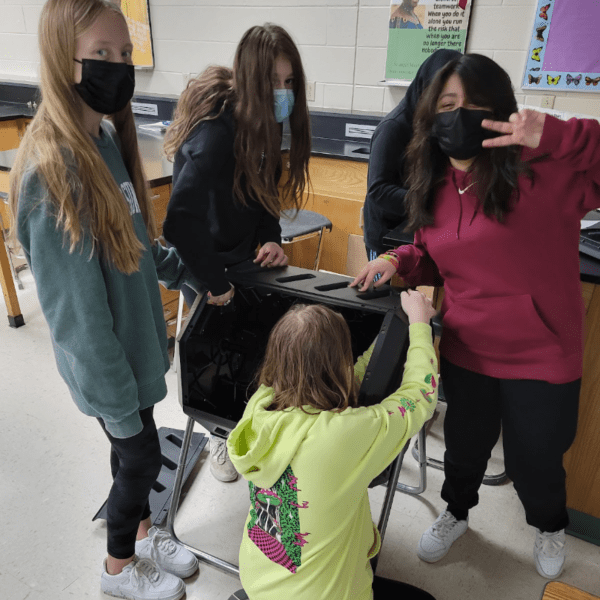

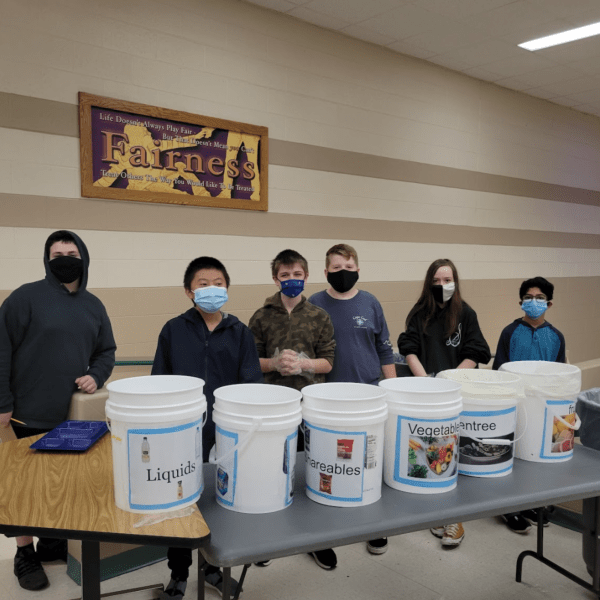

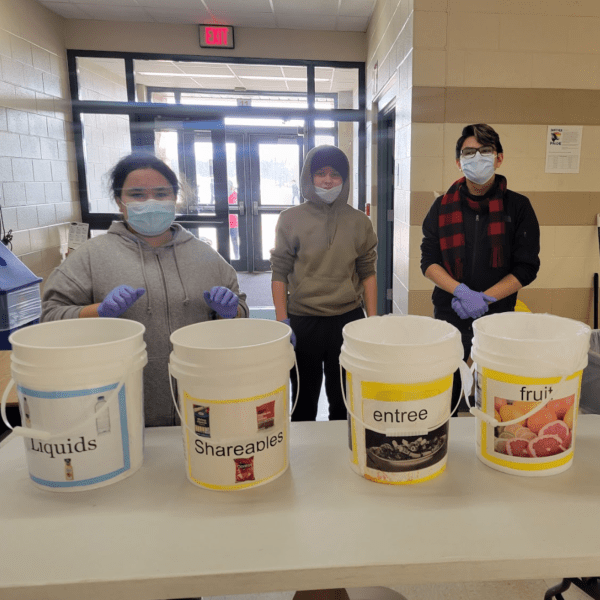

A couple of things that stand out to me: One is doing the audits. We had two stations set up in the cafeteria. We have like three tiers of the room, one in the top and one in the middle. Students would bring up their whole trays of food and whatever was on it, they would hand it to the students who are doing the audit (those are students who were in my classroom), and they would sort everything. I think I have some pictures of that somewhere in the slides, but they would sort everything and they were somewhat grossed out by it. There's a lot of “ew” and I’m like “You volunteered for this. It’s okay.” We had gloves and everything, but they were kind of in the swing of it. They would grab, put it in. I remember the first time I had done it in Cincinnati and even the first time I did it at school. I was nervous and it was going to be a lot at once. We don't know what's going to happen, and I trained the students on this is what it should look like, but they don't really know until we get there.

Carrie:

NAAEE and Stanford University partnered on an initiative called eeWORKS, which distills hundreds of research papers on the impact of environmental education. This collection of studies, “The Benefits of Environmental Education for K–12 Students,” show that hands-on programs, like what you did with your students, Angela, have been shown to improve knowledge in science, mathematics, reading, writing, and more. This seems like an experience that gave students that hands-on opportunity to work with data and get more comfortable with it.

Angela:

They were very adamant about making sure everything was in the right spot. They would ask me all these questions about where things should go. They wanted to do it well. I emphasized that this data is going to be used for the grant which is collecting data nationwide. It's going to be used to tell us what we need to change in our cafeteria, so they took it really seriously but they still had fun with it. There was a lot of laughing. There was a lot of “Hey, will you help me pull my mask” because they were standing there with like gloves on and ketchup and whatever else they have been touching.

I think they had a lot of fun with that, just being hands-on, and then having the data. Then we sat down and even though I had already plugged in all the data, I made them do it all by hand. When you collect qualitative data, there’s a lot of numbers. In the first round, we also did qualitative data, so they realized how hard that was, trying to figure out why people didn't eat the food they were, and how do we group different responses together. I think that was a really great learning tool. Quantitative data is kind of easy sometimes. We have numbers, that’s it. It’s very clear-cut, but when we get the qualitative data, how do we put this together? We only had one person out of 80 say a lactose response—Do we make that its own category? No. That might be an “Other” and something that we have to maybe emphasize.

I think it was great seeing them actually sit down and look at the data, too. Not just collect it but then sit down. I did it in six groups in my classroom and I have these big lab station tables that you see in the typical science room. They have these big pieces of chart paper, and they’re counting, and there’s one person trying to tally and another person saying what each thing was. So it was really fun to hear them and to see them work with the data and how they were all engaged, and how much data they actually go through even though I had six tables. We had six rounds of audits that first time. They each were doing a different day and that was fun. It was fast-paced because we only had 40 minutes the day that we did it. I think that they kind of liked that that was stuff that they collected. It wasn't just data that we got out of the textbook. It wasn't even a math class. This is like data that they collected in science and the real world, and it was going to be used. So I think that was really fun.

Carrie:

You worked so diligently with your students this past year. What do you think the future of this program at Patrick Marsh Middle School looks like going forward?

Angela:

I think the students who did the Food Share table will see it there and use it really easily. I think I kind of told you there were a lot of kids who wanted to take stuff off of it. And it’s right next to the garbage container so people can put stuff in. I think it’s more of a reminder of the expectations of what should go on it. We would have these hard containers with lids that come on and off and kids would sometimes put those things in there. So there were grapes but you’re not —because it's openable— they’re not supposed to be in there. So I think that they'll remember that concept. I would like to push the composting a little bit more. I think the kids who participated in the audit will not forget that time where they had to go through everybody’s garbage and sort it.

think it’s something they’ll definitely remember.

I feel like we made a lot of good changes that are going to stay at our school and reduce food in the long term. I'm hoping that our pilot of the Food Share table will go to the other middle schools and my last school, so I think that those are kind of long-term changes that we'll see in the school district through this project. But I would have liked it to have been a little more community-based and not just school-based.

Carrie:

You mentioned the process of doing the audit from start to finish was a really good learning opportunity for your students. What else were they able to do in your Community Action Plan that you think will stick with them?

Angela:

The other thing that stood out to me is when they did the Composting Seminar at the library. There were like 30 to 40 people there coming in to listen to the students. I kept telling them the max was 25 but they wanted to add more people who had signed up so there was like this big waiting list. Then they opened it up to 40 and it was full. They were so nervous about it and they're like “What are they going to think?” “It's just going to be a lot of older people, it'll be fine.”

We practiced a bunch of times, but we got to the library and they did such a good job. It was great seeing them go up there and they were all like “I don't want to do it!” “No, you’ll be fine.” Most of them talk pretty loudly. I would say they needed to like slow down, but they got up and they had a podium and they had the slides up and somebody was in charge of the projector. They were even willing to answer questions from the community, which is really great. They would ask some questions and a lot of people were interested in what they had done because we had talked a little bit about the Food Share table and the pieces we did at school. A couple of seconds after they asked a question, there would always be one student who's like, “I'm willing to talk about it” and go.

So it's really neat to see their presentation skills since we didn't do as much presenting in my class but having a practice that. A big thing one of my students said, and I think a few other ones have said it as well, is the ability to communicate my knowledge about something, having to do research, and the presentation skills. This is something that for me, I'm like “Oh yeah, we helped the environment. We did all this.” But to them what they learn from this is the ability to communicate their findings and being able to present to groups of people, that they grew in that capacity. That's something that, yeah, I know that they're going to do that but that's not something in my mind that was a “learning target,” so for them to like find that as like the piece that they're going to take away. Not all of them are going to be environmental scientists— as much as I want them to be— but something that they'll take away is that “Oh I really improved in my presentation skills and having to show my findings.” I was very adamant about that. We are not putting lots of words on slides. There are reasons why people come to presentations, they listen to you present. So that was something that I constantly was drilling into them that we need to refine what we're going to say and use that as a visual, right? And that's kind of what I always try to do with them.

[Excerpts from school podcast]

[LUNCH ROOM NOISES]

Student 1:

Getting ready for the presentations or like adding on, and not getting any information wrong, and trying to get the best information we can get.

Student 2:

Making sure that kids composted stuff, because I remember I was like, ‘Have you composted’ and stuff and they would roll their eyes at me or throw their milk cartons at me. It wasn’t nice.

Angela:

Just getting them to change their behavior.

Student 2:

Yeah.

Student 3:

I was talking to my parents and I was like maybe we could do a composting pile in our backyard.

Angela:

So I think that was kind of a big piece for me. It was a nice reflection to hear them all talking in that podcast about what they learned and what they wanted to take away from the project that we had started in October and this is May. So I liked it.

[ANGELA CHUCKLES]

Carrie:

It sounds like a really big, beautiful project you were able to facilitate for your students. That’s a ton of work, what do you see as some of the key components to it being a success, both now but looking ahead?

Angela:

I think a big part of any work I've ever done is like finding partners who are going to be doing it. Especially moving schools, I needed to connect with people in the building I was leaving who could carry on this work. For the composting, I have two colleagues who were willing to give it a try. Something I just emphasized with them was if it becomes too much, don't do it or do it once a week like if you can. A little bit or trying is better than not doing it at all and it's okay if you tried it and it's too much. I honestly want them to continue composting but I also know that teachers are overworked and it's really hard. For them to be willing to like talk to me about doing it and they really were appreciative of all the stuff we've done to reduce food, and they are willing to give it a try next year, I think is really great. I'm really glad that the Food Share table should be happening next year. I'll probably check in with the Community Schools coordinator next year just to make sure he has everything he needs, but also just continual support, back to the composting piece, and supporting the educators are going to take it over while I'm trying to get it up and running.

So just leveraging those Partnerships and finding the people who you connect with. We worked with the City a little bit and the library to do the presentation. Finding those partnerships and people who can elevate your work. I also worked with an organization in Madison, that's the capital, is right next to us basically. They're doing the Food Waste Warriors Grant, too, through World Wildlife Fund so they came and shadowed us for a while. We would kind of bounce ideas back and forth, so finding other people who are doing the same work can elevate everyone. It's hard to do a food waste audit. It's intimidating honestly. I think every person I've ever talked to about is like “Oh my gosh, that’s so much work.” Especially being an educator in a classroom, and then adding those things in, but actually it's still a lot easier once you like to see it or talk to somebody who's done it. Just give it a try.

Carrie:

Since first speaking with Angela, the Food Waste program has received lots of attention for what it’s accomplished. In total, the students were able to have a potential reduction of food waste of nearly 60%. Following the audit, these students helped launch the City of Sun Prairie’s first annual compost bin sale by presenting to the community on how to compost. And beyond that, these students were recognized for their work with multiple awards in 2022. The Dane County Office of Energy and Renewables named them a Climate Champion and Sustain Dane presented them with a Live Forward award in 2022. And when it comes to planning for future community action projects, Angela shared her perspective on how to make a project successful:

Angela:

I think overall it’s finding those people who can elevate your work, but you can also contribute to theirs as well, and just try something that can help your community.

Carrie:

Visit us at NAAEE.org or use the bitly link at bit.ly/CEEChange if you’d like to learn more about the CEE-Change Fellowship, the ee360+ partners, or read more stories of environmental education and civic engagement.