Community Engagement in School-Based Environmental Education

Communities are a crucial part of environmental education. In May 2023, several experts from the US and other countries discussed how to strengthen community engagement in school-based environmental education.

The event facilitates a broader conversation between community leaders, nonprofits, and teachers about the benefits of school-community connections for the environment and social justice. Presentations from this event are posted on YouTube as a single video, and separately in this playlist.

Below you will find: (1) links for individual presentations, (2) presentation slides, and (3) essays submitted by presenters.

Table of Contents:

2. Greening Education Partnership, Fostering School-Community Engagement—Won Jung Byun

3. Growing Community Leaders through School-Based, Hydroponic Agriculture—Renae Cairns

5. Strengthening School-Community Links through a Whole School Approach—Rosalie Gwen Mathie

6. Youth Empowerment and Climate Education Benefits Communities—Elissa Teles Muñoz

7. Erasing the Lines with Day of Discovery—Gerardo Salazar

8. Engage a Community through a School Garden: Shenzhen Practice—Ning Zhang

Image

1. Catalyzing Environmental and Climate Action in Schools Requires Communities Moving from Adversaries to Allies

Andra Yeghoian, Chief Innovation Officer, Ten Strands, USA

As an educator dedicated to inspiring students and school communities to take environmental action, I've encountered my fair share of resistance. Through years of trial and error in various roles, I've come to understand that fostering environmental and climate action in schools requires a mindset of collaborative allyship, rather than an adversarial approach.

In my early years as a teacher (2005–2010), I brought environmental and climate literacy into my humanities classes. While my students were eager to learn and take action on the environmental and climate crisis, the idea of implementing eco-friendly practices schoolwide was often met by resistance from the administration. Recognizing the need to improve my communication skills with administrators and management, I pursued a Master of Business Administration (MBA) at Presidio Graduate School, focusing on environmental sustainability and leading change. Equipped with new knowledge and skills, I successfully collaborated with my administration, enabling my students to lead impactful initiatives and establish an outdoor classroom with support from parents and community partners.

In my next role as a site-level director of sustainability, I aimed to bring transformative whole-school change—across the campus, curriculum, community, and culture. Leading change initiatives from a junior administrative position meant that I could not afford to pit stakeholders against one another. My change efforts had to be visionary and inclusive, utilize the right message for each audience, and effectively engage the greater community as partners. I also learned to embrace the reality that change occurs at varying paces and developed programs that accommodated diverse levels of buy-in and skills to drive change.

Following four transformative years in this role, I had the opportunity to expand my efforts county-wide, engaging with multiple districts and schools, and a wide range of community partners. As an external capacity builder and technical assistance provider, I encountered common patterns of adversarial relationships between grassroots efforts and resistant leaders. To address this, I established programs and networks that empowered leadership at all levels and fostered a common vision and language. I worked with frustrated and isolated folks at the grassroots levels to identify data driven and equity aligned tactics and strategies that could break through the status quo stuck points. And I helped administrators navigate around siloed structures to build new ways of seeing their school community as a whole system, where the campus can be a laboratory for learning, and where policy and partnerships could be leveraged to change behaviors for a healthier and more sustainable paradigm.

In time I found how to develop structures and processes that have been replicated and adapted across many different contexts. I now work at Ten Strands to support leaders across California to develop inclusive initiatives, collaborative networks, and visionary leadership that engage constituents as allies instead of adversaries, and transforms educational institutions into laboratories of learning and engines of sustainable change.

Resources to Explore:

- 4Cs Framework for Environmental and Climate Action in Schools

- Change Theory for Solutionary Leaders

- How to Lead Effective District-Wide Sustainability Committees

- Vision Activities for Environmental and Climate Action Initiatives

Additional resources

- Change Theories of Solitionaries — Google Doc

- The World Becomes What We Teach — book website

2. Greening Education Partnership, Fostering School-Community Engagement

Won Jung Byun, Programme Specialist, Section of Education for Sustainable Development, UNESCO

In an increasingly complex and interconnected world with a real, existential threat such as climate change, there is a growing call for education to enable individuals, as agents of change, to acquire knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes that lead to the green transition of our societies, as enshrined in SDG Target 4.7, and, indeed, in the entire 2030 Agenda. However, recent UNESCO findings show that around half of the 100 countries reviewed had no climate change mentioned in their national curriculum frameworks. As the UN lead agency on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), UNESCO is leading the global efforts on “Education for Sustainable Development: towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals” (ESD for 2030). Emerging from the Action Track 2 discussion of the UN Secretary General’s Transforming Education Summit in September 2022, the Greening Education Partnership was launched as a global initiative to respond to this urgent call. The Greening Education Partnership aims to deliver strong, coordinated, and comprehensive action on education’s role to tackle climate change. Taking a lifelong learning approach starting from pre-primary to adult education, the Greening Education Partnership encourages countries and key stakeholders to focus on 4 action areas: Greening Schools, Greening Curriculum, Greening Teacher training and Education Systems’ Capacity, Greening Communities.

The whole-institution approach lies at the centre of this roadmap to lead the transformation of learning institutions into “green schools”, which is defined as an educational institution that promotes knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes for social, economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development in its teaching and learning, facilities and operations, school governance and community partnerships. In particular, community partnership involves school becoming innovation hubs for promoting sustainability in the local communities, and the communities becoming action-learning grounds for students and teachers to help enhance the quality and relevance of learning. School-community engagement supports the transformation of the culture of the learning institution towards collaboration, solidarity, inclusion, sustainable practices so that students can learn what they live and live what they learn.

Image

3. Growing Community Leaders through School-Based, Hydroponic Agriculture

Renae Cairns, Manager, Teens for Food Justice, New York City

Photo above shows three teens displaying their harvest. Photo credit: Jessica DiMento

Teens for Food Justice (TFFJ) believes in the power of youth to lead themselves and their communities to a food-secure future. TFFJ fights food insecurity and diet-related disease through school-based, youth-led hydroponic farming, providing local, sustainably-grown produce to food insecure communities while building health equity for all New Yorkers and beyond. TFFJ works within Title I middle and high schools—schools in which at least 40% of students qualify for free or reduced price lunch - located in neighborhoods with limited healthy food access. Through comprehensive programming, students are trained to build and maintain indoor hydroponic farms, each capable of growing up to 10,000 pounds of produce annually that is served daily at school lunch and distributed to nearby community residents. Further, students learn nutrition, health, and advocacy skills, empowering them to lead themselves and others towards healthier futures.

Schools are natural centers of community. Therefore, schools and their students are uniquely positioned to address community-level challenges, such as food and nutrition insecurity, physical and mental health disparities, and environmental racism. By taking a comprehensive approach to engaging students in school-based, youth-led urban agriculture, TFFJ’s program honors and helps to activate the assets young people and schools bring to their community. Through inclusive community needs assessments and multi-stakeholder collaboration, underutilized spaces in schools are transformed into sites of healthy food production. By nurturing a plant through its life cycle, students become agents in changing what is consumed by themselves and their peers during school lunch. Through advocacy training and skill-building, students grow into food justice advocates addressing the aforementioned community-level challenges that are experienced both within and beyond school walls.

Through our holistic approach, TFFJ supports students and schools as active and impactful members of their broader communities, equipped with the skills and resources to meet both immediate and structural community needs.

Image

4. The Benefits of School-Community Partnerships for Equitable Environmental Literacy

Candice Dickens-Russell, President and CEO, Friends of the LA River

School and community based organization partnerships provide valuable opportunities for both entities to meet their goals and to increase equitable environmental literacy for students. Teachers can depend upon local environmental organizations to provide content and context for lessons in a variety of topics, provide true partnership in deepening student knowledge, and provide hands-on educational experiences. This is especially beneficial when school districts seek partnerships with organizations, and provide their teachers vetted resources relevant to the subject matter. Environmental education organizations are often funded based upon the number of students they can engage in their programs and projects. This provides an incentive to develop high quality programs that teachers will see as a value add to the work being done in their classrooms. Likewise, teachers are often lacking resources and time. Resources like mobile museums, touch tanks, and highly trained education staff are readily available at many CBOs with environmental programs, and most are eager to partner with schools. Some benefits of school/community partnerships:

- Access to experts and resources: Community-based organizations often have experts who specialize in various environmental fields, who can provide valuable knowledge and resources.

- Real-world examples: Community-based organizations are often actively involved in local environmental issues and initiatives. Working with them can provide students with opportunities to learn about real-world examples of environmental problems and solutions in their own communities.

- Field trips and experiential learning: Many community-based organizations offer field trips and experiential learning opportunities that can help students connect with nature and learn about environmental issues in a hands-on way. These experiences can be particularly impactful in fostering a sense of stewardship and responsibility for the environment.

- Community engagement: Partnering with community-based organizations can also provide opportunities for students to engage with their local communities and learn about the interconnectedness of environmental issues with social justice and equity. This can help students understand the importance of environmental sustainability in building more resilient and equitable communities.

Overall, partnerships with community-based organizations can help schools enhance their curriculum, provide students with valuable experiences, and foster a deeper understanding of environmental issues.

Image

5. Strengthening School-Community Links through a Whole School Approach

Rosalie Gwen Mathie, Researcher, Norwegian University of Life Sciences

How can schools support sustainability-oriented transformations asked of their local communities? And vice versa, how can communities support their schools to embrace the local community as a classroom? A Whole School Approach (WSA) to sustainability-oriented education provides a powerful transition pathway towards education that is relevant, responsive, responsible, and regenerative. Figure 1 offers a WSA model featuring the strands of an institution required to proactively engage with sustainability-oriented education, alongside key enabling policies to support schools integrating such an approach (Mathie & Wals, 2022).

A WSA in essence can be used as a thinking tool, whereby multiple distinct but interconnected educational innovations asked of schools and communities today, such as environmental education, global citizenship, health and wellbeing, can be integrated in a way that is mutually supportive instead of competing. Reflexive questions related to each WSA strand offer a starting point for discussing the individual and institutional roles required to support transformation toward sustainability:

- Institutional Practices - What does a sustainable location imply for how we interact, structure, and utilise our surroundings to co-create place-based sustainability?

- Capacity building - What does a sustainable institute imply for the type of continuous professional development of all our staff?

- Community links - What does a sustainable institute imply for how we involve the local community and society further afield?

- Curriculum - What does sustainable education and learning imply for what we teach, measure, and assess?

- Pedagogy and Learning - What does a sustainable institute imply for how and where we teach and learn?

- Visions, Ethos, Leadership & Coordination - Institutional culture and ethos need to align with the vision. Consistency between thinking and doing is essential. What does a sustainable institute imply for how we coordinate, operate, and lead?

Through reflexive dialogue mutually supportive school-community links can be strengthened, whereby the local community supports the education of its inhabitants, and in turn the school can authentically participate in sustainability-oriented regeneration. For practical examples of schools engaging with a WSA around the world please visit our Whole School Approaches page.

Mathie, R. G. and Wals, A.E.J. (2022) Whole School Approaches to Sustainability: Exemplary Practices from around the world. Wageningen: Education & Learning Sciences/Wageningen University. 109 pages. https://doi.org/10.18174/572267

Wals, A. E. J., & Mathie, R. G. (2022). Whole School Responses to Climate Urgency and Related Sustainability Challenges. In M. A. Peters & R. Heraud (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Educational Innovation (pp. 1-8). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2262-4_263-1

Rosalie’s reflections after the Expert Panel:

- In order to move away from the more common bolt on approach to sustainability education, what is taught in the classroom needs to be echoed and experienced elsewhere around the school and in the wider community.

- Like the UNESCO tag line goes, in this context we need to live what we learn.

- This WSA flower model features six interconnected strands of an institution that are required to proactively engage with sustainability-oriented education to support this type of holistic approach.

- In essence a WSA is a thinking tool for quality education, whereby multiple educational innovations asked of schools and communities today, such as environmental education, global citizenship, health and wellbeing, can be integrated in a way that is mutually supportive instead of competing.

- I think this broad understanding of a WSA is very key to overcoming and moving on from this bolt on response.

This is a call for all stakeholders to understand how the community can serve the school and vice versa how the schools, and all those who are part of this, can serve the community. As Biesta’s book on World Centered Education describes and explore “[…] the importance of teaching, not understood as the transmission of knowledge and skills but as an act of (re)directing the attention of students to the world, so that they may encounter what the world is asking from them.”

- Reflexive dialogue is a great foundation for strengthening school-community links. Studies show that having the space for us to learn from and with each other, peer to peer learning and professional development is a key part of integrating effective institutional change.

- Finding the capacity, and time for key community and school stakeholders to be reflexive together, to find ways for students to be part of authentic sustainability transformations, in action, in practice, is vital in this context.

For example, consider reflexive questions and statements connected to the six whole school approach strands to assist in understanding a school’s and local community’s current practice and culture. Through this, concrete places, spaces, and ideas where school-community links can be strengthened, can be established:

(Reflexive questions adapted from Wals & Mathie, 2022)

Image

6. Youth Empowerment and Climate Education Benefits Communities

Elissa Teles Muñoz, Consultant, National Wildlife Federation

The current generation of young people all over the world are at a critical juncture: while constantly told that they are “the future,” they often lack formal and interdisciplinary education about topics related to climate change in the classroom. Many young people are anxious, dissatisfied with their governments, and frightened by the prospect of inheriting a burdensome future. It is time to envision meaningful education frameworks at various scales that promote the empowerment of youth and the development of green skills, defined by the United Nations as the “knowledge, abilities, values, and attitudes needed to live in, develop, and support a sustainable and resource-efficient society.” The Climate and Resilience Education Task Force (CRETF) and our Youth Steering Committee seek to realize this vision in New York State’s P–12 schools.

As their adult mentor, I guide our Youth Steering Committee students to use a systems thinking lens to reflect on the quality of education they’ve received in their P–12 careers. For example, do they agree that students are the most important stakeholders in the education system as it presently exists? If not, what should change, and why? Following these constantly-evolving conversations, and armed with conceptual bases of collective efficacy and individual agency, the students take on advocacy projects for their own climate education, and for the education of future generations of students, at the state and city levels. Together, we engage in conversations with elected officials, state and city governments, and New York State education decision-makers.

Climate education and civic engagement promote a sense of collective efficacy among educators, students, their families, and the wider community. Addressing complex global challenges requires individuals to confront existing socio-economic systems and prevailing cultural norms. Moreover, empowering students to impact their communities begins with entrusting them with the ability to develop the agency to engage in systemic change. The students I’ve been lucky to work with are guided by the understanding that they have an important role to play. For many of them, the climate education they’ve received in our program or at another point in their lives has blossomed into climate action projects in their communities. Through their political advocacy and other projects, our students are developing skills necessary for transformative, community-based change such as public speaking, leadership, empathy, systems thinking, emotional attunement, and collaboration.

Image

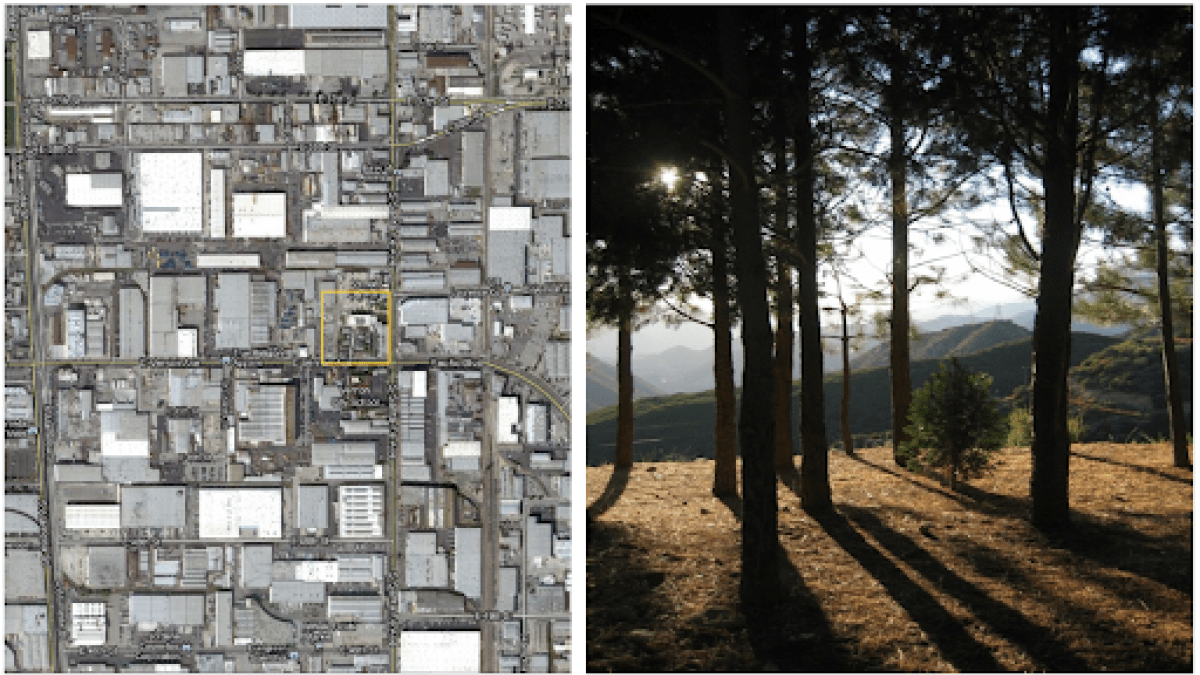

7. Erasing the Lines with Day of Discovery

Gerardo Salazar, Administrator, Los Angeles Unified School District, USA

No longer is it enough to learn by memorization and rote exercise. Students must now have a working knowledge of science, math, English Language Arts and social studies. Expertise in these content areas abounds within our 715-mile enrollment boundary. In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), Superintendent Alberto Carvalho has made the mantra every child “ready for the world” the focal point of the strategic plan. As a District administrator, it has been my joy to blur, and in some cases erase, the lines by formally integrating resources of community-based organizations with the school day. Children will be ready for the world when we make a deliberate effort to have them experience it.

Day of Discovery Programs were born out of necessity. Clear Creek Outdoor Education Center, LAUSD’s overnight science camp, had a 5 year wait list in 2016. What if all the schools that didn’t get to go to camp, had an opportunity to go to a place that allowed them to explore the natural world? The search for more field study sites was driven by questions about educational value, costs, and safety but the one question we always came back to was…Where would our inner 10-year-old like to visit but never got the chance? As of 2019, with the collaboration and support of our partner community-based organizations, nine Day of Discovery Program sites have offered year-round (including summer) outdoor education opportunities for thousands of LAUSD students and teachers. All partners shared the vision that these were not tours of a site or venue, all programs are to be field study opportunities where children went to “do science and experience nature.”

Partnerships and collaborations with community-based organizations are based on:

- Established compatibility: Parties agree to understand and support one another’s mission, vision, values and intended outcomes.

- Dynamic Collaborations: partner sites and programs have become synonymous with LAUSD educational opportunities. Daily communications and District support with training and curriculum development is the norm.

- Collective sense of purpose: partners work to support our Academic Excellence and Joy and Wellness

- Mutual Support: Our office works to support the grant and fund-raising efforts of our partners.

Integrating, normalizing and formalizing outdoor education in and around Los Angeles is a scaffold for children to have a sense of local pride and personal investment. Children are learning all the time- everywhere. Without the support of community-based organizations, the dream of Outdoor Education for all, Kindergarten through 12, is not possible.

Image

8. Engage a Community through a School Garden: Shenzhen Practice

Ning Zhang, Program Director, DreamEcoLand, Shenzhen, China

Xiantian Banmu is a school garden located in Xiantian Foreign Studies School (K12), Shenzhen, China. It is one of the 360 Co-Building Gardens built within last 3 years. Co-Building Garden Program, initiated by Shenzhen Urban Management Burau in 2020, aims to build more than 100 public-participating gardens each year and encourage different government departments, communities, schools, charitable organizations and local business to participate.

The garden, located in the atrium of the teaching building, was 15 different-sized raised beds with grass. We invited key stakeholders to participate in all stages. In Oct 2021, we organized a design workshop with students and teachers, learning that they had a strong urge in planting vegetables and fruits. In Nov 2021, almost 100 volunteers from teachers, students and their parents constructed the garden together.

Three beds were repurposed as a wooden platform, a flowery resting area and am observation pond. The rest were turned into small farmland (approximately 3 square meters each), and assigned to 28 classes from grade 1 to 5 as class ziliudi (class private plot).

From 2022, all the class ziliudis are planted managed by students. In spring 2023, school decided to plant the same plant for each grade: soybean, corn, peanuts and mugworts for grade 1–4. Parents come to help happily once a month with heavy duties. Teachers develops school-based curriculums, such as Learning the Twenty-Four Solar Terms by Planting. The garden won a third prize among 120 gardens.

As a fast developing city, 65% of Shenzhen’s population moved in within last decade, which leads to loose community structure. Schools have a great potential to act as a community center and promote environmental actions such as gardening. It is also a great way to let children improve their unnatural and plain school environment, as a practice of civic engagement.

Acknowledgement

The expert panel is funded by the Office of Environmental Education at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through ee360+, the environmental educator training program led by the North American Association for Environmental Education under Assistance Agreement No. NT 84019001. This expert panel has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed in this expert panel are solely those of the panelists and facilitators. EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this panel.

Join eePRO today and be a part of the conversation!

Comment and connect with fellow professionals in environmental education. Join eePRO >