From Seed to System: Designing Sustainability Education for Broader Impact

Picture a familiar scene: an older public school building, humming fluorescent lights, the faint smell of cafeteria lunch in the hallway. Then you open one classroom door and the mood shifts. It’s brighter, greener, and busy with purposeful work. Students are tracking growth, troubleshooting a system, and deciding what to plant next. The project is hands-on. It also treats school as a place to practice solving real problems.

That is the focus of a new open-access case study, “Systemic Impacts of Sustainability Education: A Case Study of New York Sun Works” (Journal of Environmental Education, 2025). The authors examine New York Sun Works (NYSW), a nonprofit that supports sustainability science learning in NYC public schools through classroom hydroponics, teacher professional development, and a K–12 curriculum. The study draws on interviews (including this narrative video with Manuela Zamora, NYSW Executive Director), teacher perspectives, and observations.

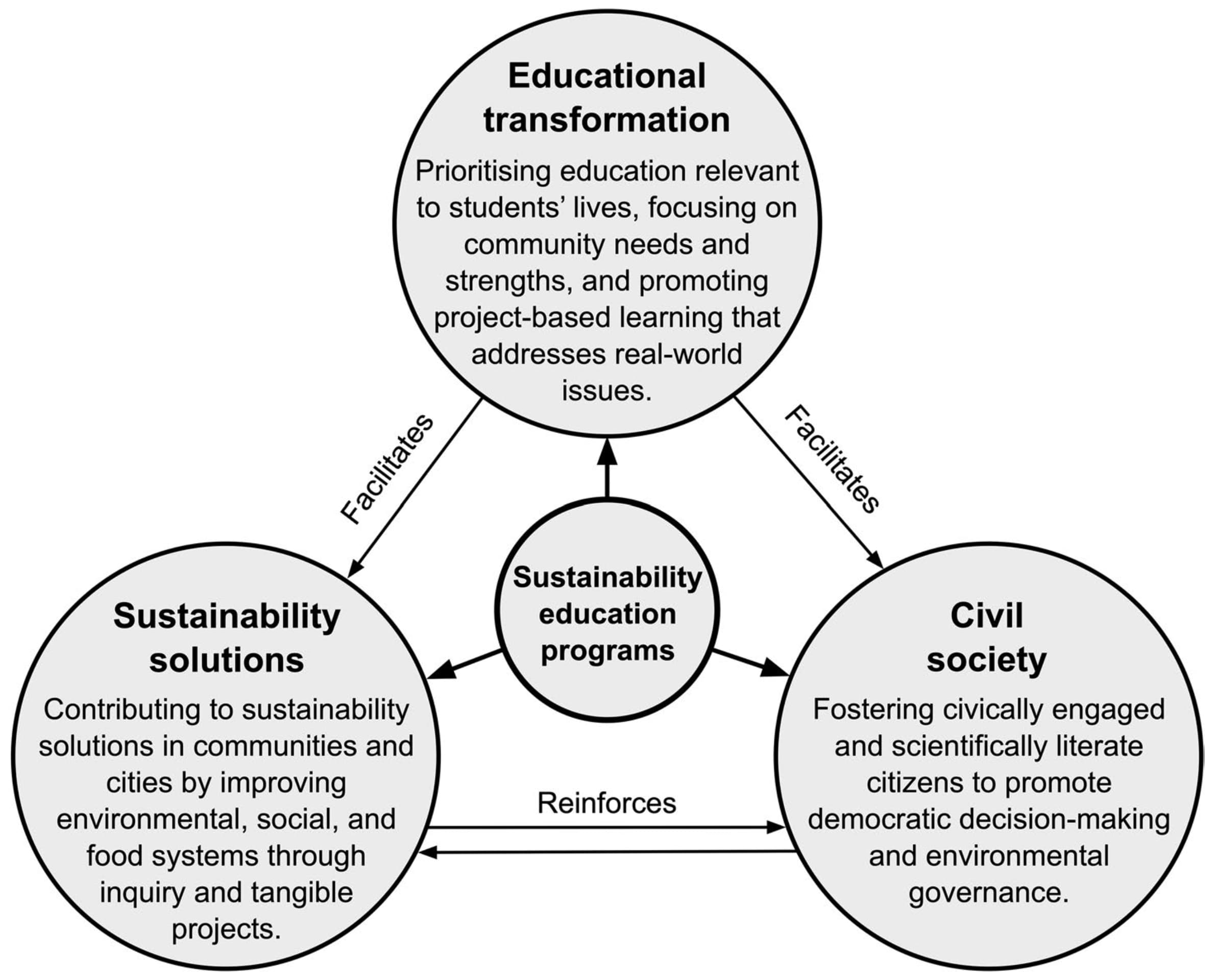

The paper’s main contribution is a framework that helps environmental educators look beyond short-term outcomes. The authors describe three domains of system-level impact that sustainability education can support. First, educational transformation: learning becomes more relevant to students’ lives, strengths, cultures, and interests, often through project-based work and student agency. Second, sustainability solutions: schools can operate as living labs where students test and share practical solutions connected to food, waste, health, and local needs. Third, civil society: students practice participation, decision-making, and collective action, building the skills of civic engagement early.

The authors are explicit that system-level impacts are hard to measure and hard to link to one program through simple pre/post tests. Yet the framework is still useful because it guides program design. It helps educators connect daily activities and measurable outcomes to long-term goals and the broader changes they hope to see in the environment and society.

The case of New York Sun Works can also offer practical insights that apply beyond hydroponics. Even without a specialized lab or a large partner organization, environmental educators can design learning that connects students’ lives to real-world problem-solving and shared decision-making. Here is one classroom practice you can adapt to almost any environmental topic:

- Start with a lived local question (1 class period). Ask students to choose a question they see in their own school or community (food access, waste, heat, water, habitat, transportation, energy use). Have them gather quick evidence: a short survey, a few observations, a photo audit, or a simple data log.

- Create many ways to lead (ongoing). Assign roles or let students choose how they will contribute through different strengths: investigators, builders/makers, data trackers, storytellers, designers, connectors to community, or facilitators.

- Build a small solution prototype (2–3 class periods). Keep it modest but connected to real problems: a redesigned recycling/signage system, a pollinator conservation plan, a cafeteria waste reduction test, a water-saving practice trial, a community resource map, or a small “school farmers market” pilot. Students test it, adjust it, and explain how it could help in their community.

- Practice one civic action (1 class period). Students make a decision together (what to prioritize, who benefits, how to share results), then communicate it outside the classroom through a short letter, a poster session for staff, a brief presentation to a principal or partner, or an invitation for a local leader to visit.

- Document the story as you go (ongoing). Save a few artifacts (photos, student quotes, before/after data, a reflection) so you can show educational growth, a practical improvement, and early civic participation without claiming perfect attribution.

These activities support educational transformation (agency and relevance), sustainability solutions (real-world testing), and civil society (shared decisions and public communication), while staying realistic about what you can measure in a school setting.

Explore the case (and see it in action):

- Journal article (DOI): https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2025.2567395

- Video interview (YouTube): https://youtu.be/ymkioZ92ino

- Podcast episode: https://youtu.be/GiddGqTageU