Weathering the COVID-19 Storm: Adapting Educational Experiences at 21st Century Community Learning Centers

eeBLUE: Watershed Chronicles

This post was written by David Kline, Watershed Education Specialist at Stroud Water Research Center.

Stroud™ Water Research Center seeks to advance knowledge and stewardship of freshwater systems through global research, education, and watershed restoration. This three-pronged approach provides a uniquely collaborative ecosystem for making a difference on our planet. Scientists at the Stroud Center work to understand the complexities of freshwater ecosystems and identify actions to improve and protect the health of our watersheds. The restoration team works with various stakeholders to implement best management practices to restore damaged waters and preserve watershed ecosystems.

Our education team, meanwhile, energetically interprets the expertise of our research and restoration scientists and disseminates the knowledge to audiences of all ages. As a NOAA-funded partner, we collaborate with environmental education leaders and task forces across Pennsylvania to develop and deliver programs that enhance environmental literacy and expand the use of the Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience (MWEE) curricular framework. When the opportunity arose to participate in the new eeBLUE grant program and bring enriching watershed-focused education in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) to 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLCs), we were ecstatic!

Located in the Upland Piedmont Province of southeastern Pennsylvania, the Stroud Center is nestled in bucolic horse country and adjacent to Kennett Square, the self-proclaimed mushroom capital of the world. The region is home to a large migrant farming workforce, the state’s highest density of Latinx populations, and a nearby old steel town with significantly underserved populations.

NOAA eeBLUE grant funding has engineered a pivotal new pathway and partnership to connect us to these local communities: 21st CCLCs that serve Title 1 economically disadvantaged students in the Stroud Center’s backyard watersheds. One local center primarily serves English Language Learners (ELL) whose families mostly speak Mayan dialects and may have limited literacy in their primary language. Many of these students are learning Spanish and English at the same time. Needless to say, challenges were present before the introduction of COVID-19 into the story.

Our goal was to pilot programs at three 21st CCLC sites (a migrant education summer camp for high school students, an elementary school, and a middle school) and then develop three levels of watershed STEM programming with embedded MWEEs (elementary, middle, and high school level). To close the loop of learning for youth and sustain their excitement from the first spark of inquiry to real-world action in their local watershed, each program would include the four essential elements of the MWEE framework: issue definition, outdoor field experiences, synthesis and conclusion, and stewardship and civic action. NOAA eeBLUE funding for this grant would allow for in-person excursions to local river sites for boots-in-water stream studies, which provide keystone outdoor field experiences where students become stream scientists.

Then, the pandemic entered the picture, schools closed their doors, and the world was launched into a virtual teaching landscape overnight. Our planned in-person programming had to be rewritten and adapted for an entirely online, at-home learning setting. While piloting virtual lessons over the next year, our educators and students alike grappled with challenges such as virtual learning fatigue, electronic device limitations, language barriers, and the difficulty of converting authentic outdoor field experiences to an online environment.

Like the innovative and resilient network of environmental educators at NAAEE, the Stroud Center prides itself on perceiving obstacles as opportunities for innovative problem-solving. What follows are some of our richest lessons learned through watershed STEM education throughout two years (and counting!) of a pandemic.

Incorporate Icebreakers! Whether navigating Zoom fatigue or language barriers, the best way to make an early impression is to emphasize fun. Pictures are worth a thousand words in any language, so the inclusion of fun—sometimes silly icebreakers—can profoundly affect youth morale and engagement. A quick check-in using a “scale of squirrels” or “which superhero do you identify with most” can put a smile on most faces.

Take Nature Breaks! Who says we cannot take students outside…virtually? Including interactive videos like this 5-minute Pause on the Planet brings the soothing sounds of nature inside, gets kids out of their seats, invigorates blood flow, and stimulates the senses for learning. See our Assistant Director of Education, Tara Muenz’s True Nature YouTube channel, for more examples.

It Takes Two…Instructors! Just as two heads are better than one, we found that at least two instructors are a best practice in virtual and in-person education settings alike. Extra staffing allows for easy transitions between activities, provides real-time monitoring and sharing of information or responses from the chat window, creates a more dynamic learning environment that helps to hold everyone’s attention, and enhances student buy-in altogether. This is particularly helpful when navigating language barriers, as one instructor can look for and engage timid participants, while the other instructor moves the lesson forward.

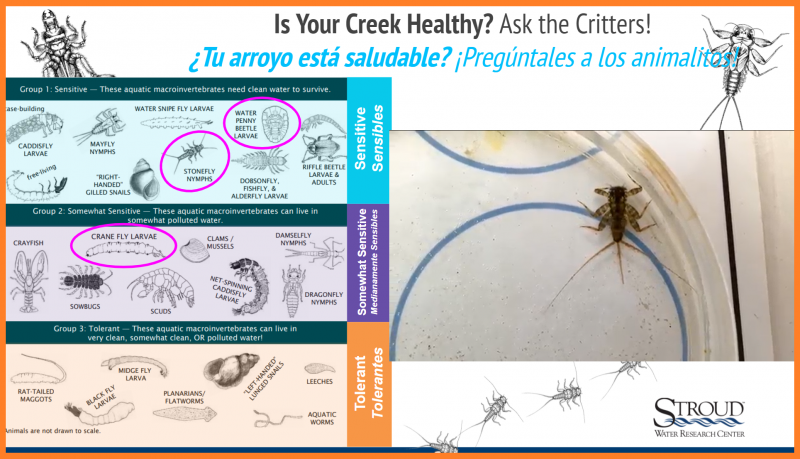

Virtualize Outdoor Field Experiences! This challenge usurped the most time and resources. We quickly realized that students need recognizable locations to develop a connection to nature and the issues we discover. If it is not their backyard, why would they care? To facilitate authentic connections between students and their local watersheds, we recorded stream studies conducted in a location they would recognize. Chemistry test results were displayed next to the color comparators so the students could actively determine the results. Videos of animated macroinvertebrates were shown one taxon at a time, and students identified each critter by matching it to a panel of graphics or using an interactive clickable dichotomous key. This stream-to-screen virtual education experience ensured that the magic did not end with boots-in-the-water in-person education.

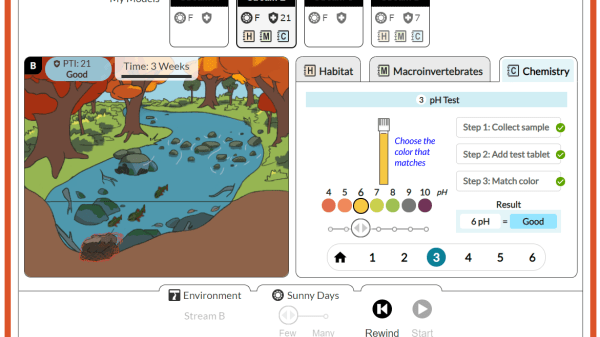

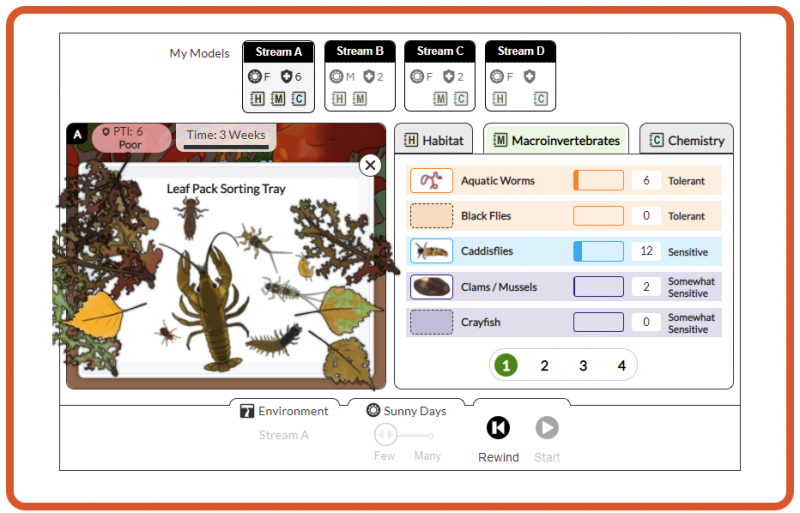

Dive into the Leaf Pack Simulation! The Stroud Center co-developed this new virtual stream study simulation to provide an alternative water quality assessment experience for online learners during the pandemic and beyond. Using this tool, students gain experience with scientific stream study methods and practice assessing the water quality of a stream. The Leaf Pack Simulation allows users to perform habitat, chemistry, and biotic assessments on four different streams. Students can pick the stream that most closely resembles a stream in their community, or run tests on various streams to compare the results.

We hope that some of these tips and tools help others provide enriching Watershed STEM programming that connects kids with nature and inspires the next generation of stewards for our planet.

The NOAA Office of Education and NAAEE partnered to increase environmental and science literacy among NOAA’s partners and external networks. In this five-year partnership supported by the U.S. Department of Education, NOAA and NAAEE worked together to provide enriching after-school watershed-related STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) projects through NOAA-21st Century Community Learning Centers Watershed STEM Education Partnership grants. These grants supported programming for a total of 100 local 21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st CCLC) sites and their students. The 30 selected projects served 18 states, ranging from Alaska to Florida.

Comments

Impressive - both in educational conclusions/suggestions and in presentation.