Combating Ecophobia in the Classroom

Growing up, most millennials heard horror stories about what humans were doing to destroy nature. From bulldozing the Amazon rainforest to the gigantic hole in the ozone layer to acid rain, the stories our teachers told us were meant to both educate us and get us to care about actions that we could take to “save the planet”. But from what I remember, my teachers in the 1990’s didn’t really have any solutions for what could be done to “save the planet” beyond the three R’s (reduce, reuse, recycle) and picking up litter in local parks. This was extremely difficult to deal with as a child who loved the environment from a very young age.

I was very fortunate to grow up in a rural area surrounded by nature. I spent my summers swimming in lakes, hiking through woods, and catching caterpillars. My family went on weekend camping trips, and typically took vacations to national parks all over the United States. I credit these experiences as the primary reason for my obsession with nature today, and I imagine many environmentalists had similar experiences growing up. It can be difficult then, for people with these experiences to know how to encourage a connection with nature in others who did not have that experience as children. Many times, we as educators believe that to build that connection, children need to “put down the tablet and spend time outdoors” in unsupervised nature play1. However, this comes from a place of nostalgia, and doesn’t really take into consideration the barriers that today’s children face with that sort of experience.

Many of those activities that I participated in while growing up are privileged, since they often require specialized equipment or transportation to specific areas. Many people, both in urban and rural environments, just don’t have access to these recreational activities in nature. Additionally, a love of these activities is usually fostered by a parent or other close relative who grew up with these activities themselves. Without a close family member to help guide them, a child is much less likely to have these outdoor activities to help build their connection with nature. And even if the access was there, how many parents feel safe enough to allow their children to play outdoors? Between high traffic areas, a lack of sidewalks, and potentially unsafe neighborhoods, it’s easier for a parent to keep their kids indoors. When outdoor activities happen, they’re highly structured, and closely supervised.

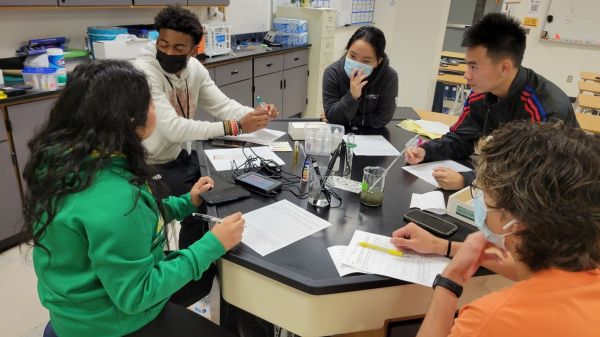

As a high school educator, I teach a year-long Aquatic Science course, where we spend a lot of time discussing different ways that humans affect aquatic ecosystems. I can see the discouragement in my students' faces when they notice the disparity between negative and positive effects humans have on local environments. Since I teach in a highly diverse school in an urban setting, many of my students don’t have a foundational connection with nature to help them care about these issues. Conservation is seen as a “white people thing”, presumably in part due to all of those outdoor activities being dominated by white people, but that doesn’t even take into consideration the racist history of the conservation movement2. So instead of asking about what actions they can take, or having the inspiration to go out and “save the planet”, they sink down in their seats and assume that nothing can really be done about it. There are two main issues here that I should address as their teacher. I need to find a different way to help them build a connection with nature, and I need to make sure to address the things my teachers did not: how people are solving environmental problems, and how anyone can help.It’s hard to be an environmentalist in today’s world. I don’t mean that it’s difficult, because in many ways it’s easier to make informed decisions to reduce waste as individuals, from buying local to supporting sustainable companies. What I mean is that it is incredibly mentally taxing to be an environmentalist today. With all of the bad news and problems happening in the world today, it can seem like an impossible task to tackle all (or even any) of the issues facing the environment.

There is a fine line to walk between being upfront and honest with students old enough to understand the impacts of human activity, and cultivating a positive attitude towards the work that needs to be done. Ecophobia was the term used in my undergraduate studies, which is a feeling of powerlessness to affect change to the vast environmental issues facing our planet3. Ecoanxiety is another term that’s become more common recently, meaning a “Chronic fear of environmental cataclysm that comes from observing the seemingly irrevocable impact of climate change”4. I have both experienced these phenomena myself, and I see it in my students on a regular basis. Much of the curriculum out there focuses on these negative impacts of humans, without offering potential solutions, which I believe makes ecophobia worse. By neglecting to discuss real avenues that scientists and activists are using to make change, we are doing a huge disservice to this new generation of budding naturalists.

So how can we as educators both emphasize the importance of caring for nature while empowering our students to enact change, ideally while also fostering that personal connection to nature?

One avenue that many educators embrace is the use of citizen science to help build connections between students and nature, while also showing how the data they collect can be used to increase our understanding of what is happening in a local ecosystem. Zooniverse5 and iNaturalist6 are two popular tools that teachers have used to bring citizen science into educational settings. Zooniverse’s game camera identification projects are easy to implement with children, who typically love spotting animals they recognize. iNaturalist in particular is enticing, since it helps get people outdoors into nature, and emphasizes that nature is present everywhere, even on school grounds and in backyards.

Another idea that teachers should implement is being conscientious of sensitive topics, and teaching only age appropriate topics with respect to human-driven ecological problems. Ecophobia is heavily influenced by teaching these topics to children who are too young to truly understand the nuances of what is happening. These topics should be slowly introduced as students get older, and then the gray areas can be truly explored as they reach high school age.

A greater emphasis should be placed on accessible outdoor activities. A love for nature can be fostered through more than just camping and hiking. Things like gardening and landscaping involve close working relationships with nature. Nature can be found near bird feeders, in parks, and hiding under the bushes down the street. If we focus on teaching students that nature is right in front of them, and that The Environment is also their immediate environment, they are so much more likely to feel that connection with nature.

To avoid discouragement from hearing all the doom and gloom related to things like climate change and plastic pollution, it’s important to offer solutions that are actively being implemented, as well as tangible actions that students can take to help. For example, when I teach about the garbage patches floating in the center of our oceans, I also show some of the technology that people have developed to prevent trash from reaching the open ocean. Things like Mr. Trash Wheel in the Chesapeake Bay7 and current research on plastic-digesting bacteria8 have helped quell some of the fears my students have. Additionally, I emphasize actions they can personally take to help, such as reducing the amount of single-use plastic they use, and volunteering for park and beach cleanups9. A great resource for tangible actions is the Drawdown Ecochallenge10. By completing simple, specific tasks, individuals and teams earn points. Those points can be used to calculate the actual, real world impact you and your team have on ecological issues. Teachers are able to create class teams to encourage community building and collaboration while working towards sustainability goals.

While it was difficult for me to recognize that my lived experience as a child growing up outside was not realistic for the majority of American families today, I am a much better environmental educator for it. We must find a way to adapt in order to reach the next generation of conservationists. By making these adjustments to curriculums, it is so much easier to inspire our young people, and help them believe that change is possible.

Citations

- Dickinson, E. (2013). The misdiagnosis: Rethinking “nature-deficit disorder”. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 7(3), 315-335.

- Gould, R.K, Phukan, I., Mendoza, M.E., Ardoin, N.M., & Pannikkar, B. (2018). Seizing opportunities to diversify conservation. Conservation Letters, 11(4), e12431.

- Estok, S. C. (2020). The ecophobia hypothesis. Routledge.

- Whitmore-Williams, S. C., Manning, C., Krygsman, K., & Speiser, M. (2017). Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e503122017-001

- Zooniverse. (2022, April). Welcome To The Zooniverse: People-Powered Research. Zooniverse. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://www.zooniverse.org/

- iNaturalist. (2022). iNaturalist: Connect with Nature. iNaturalist. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://www.inaturalist.org/

- Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore. (2022, March 21). Mr. Trash Wheel: A Proven Solution to Ocean Plastics. Mr. Trash Wheel. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://www.mrtrashwheel.com/

- Zeenat, Elahi, A., Bukhari, D. A., Shamim, S., & Rehman, A. (2021). Plastics degradation by microbes: A sustainable approach. Journal of King Saud University - Science, 33(6), 101538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101538

- Ocean Conservancy. (2022). Fighting for Trash Free Seas®. Ocean Conservancy. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://oceanconservancy.org/trash-free-seas/international-coastal-cleanup/

- ecochallenge.org. (2022). Join the drawdown Ecochallenge, presented by Ecochallenge.org. Drawdown Ecochallenge - Home Page. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://drawdown.ecochallenge.org/